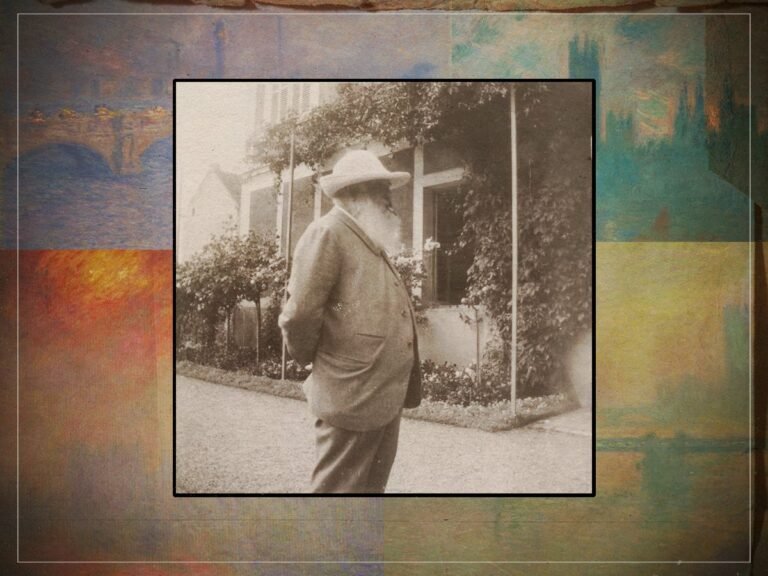

(Credits: Far Out / Art Institute of Chicago / Public Domain / Claude Monet)

When Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Effet de Brume went up for auction at Christie’s in 2022 with an estimated price tag of £24million, the art world once again turned its gaze to the Impressionist master’s famous “London series”. With its dreamy hues and blurred outlines, the painting appears to capture a quiet, poetic morning on the Thames – a serene scene where lilac fog and soft sunlight melt into one another.

But beneath the delicate pastel veneer lies a much darker truth. This isn’t just dawn, it’s a portrait of a city choking on its own modernity.

Between 1899 and 1901, Monet painted nearly 100 views of London, mesmerised not by its architecture or people, but by its atmosphere – more precisely, by its pollution. His canvases depict the city through a thick haze, casting bridges, rivers, and skies in shifting spectrums of lilac, blue, and gold.

Waterloo Bridge, Effet de Brume is one of the finest examples of this exploration. At first glance, it’s all softness and serenity. But look closer, and the illusion dissolves. In the background, barely perceptible but unmistakable once seen, are two towering factory chimneys exhaling smoke into the air.

In 1904, when Monet completed this painting, London was often shrouded in what was then known as “pea-soupers” – dense clouds of smoke and fog caused by coal-burning factories, chimneys, and trains. It’s hard to imagine it, but Victorian London, in fact, had some of the worst air pollution in the world – worse, experts say, than modern-day New Delhi. The cityscape Monet observed from his suite at the Savoy Hotel was often so obscured that he couldn’t even see the Thames below.

“It has to be said that the climate is so idiosyncratic,” Monet wrote to his wife in 1900. “You wouldn’t believe the amazing effects I have seen in the nearly two months that I have been constantly looking at this river Thames”. Those “effects” were no mere weather flukes – they were visual results of industrialisation at full throttle. And to Monet, far from discouraging him, that made London an irresistible muse.

“My practiced eye has found that objects change in appearance in a London fog more and quicker than in any other atmosphere,” he told a journalist in 1901. “The difficulty is to get every change down on canvas.”

For Monet, London’s smog symbolised something much larger than he was keen to explore: the exuberant wealth of this European capital. Here was the heart of the 19th-century global empire – the economic engine of Europe – shrouded in the consequences of its own industrial wealth. The very fog that softened and beautified his canvases was the same smoke that blackened lungs and dimmed the city’s skies.

In many ways, London was the perfect Impressionist city: thoroughly modern, economically powerful, and perpetually in flux. It was a city defined by contrasts, light and shadow, elegance and grime, wealth and ruin.

It was also a place of personal refuge. Monet first came to London in the early 1870s, escaping conscription during the Franco-Prussian War. Like many before him – Marx and Lenin among them – he found in the “Smoke” not just safety, but a strange kind of freedom, both political and artistic.

More than a century later, Waterloo Bridge, Effet de Brume, remains a haunting image – not just of a river or a bridge but of a civilisation in transformation, which remains ever so poignant at a time when climate change increasingly affects our lives. Behind its gentle palette is a powerful commentary on the costs of progress, captured by an artist who saw poetry in pollution.

Related Topics