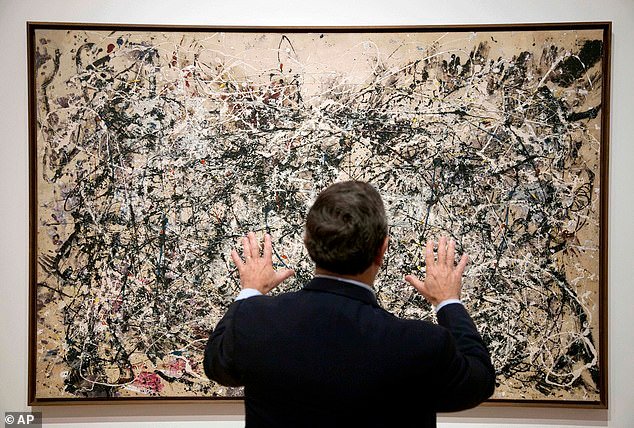

It’s one of his most celebrated paintings, and a stunning showcase of his distinctive ‘drip’ technique.

‘Number 1A, 1948’, on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, is thought to symbolise Jackson Pollock’s pure, unrestricted creative freedom.

It features dynamic swirls of oil and enamel paint, dripped from height onto the canvas – a striking image at odds with the painting’s minimalist title.

Now, 77 years on, scientists have identified the ‘extinct’ pigment that Pollock used to create the masterpiece.

They confirm for the first time that the abstract expressionist used a vibrant blue shade that’s been unavailable for decades.

It was in production from the 1930s until the 1990s, having been banned by the artistic community due to fears of toxicity.

At the time of its creation, Pollock – a troubled alcoholic for most of his life – was most likely unaware of the paint’s dangers.

But now the scientists know the exact shade, their findings offer ‘critical context for conserving his work’.

This particular painting, called ‘Number 1A, 1948’, showcases Pollock’s classic ‘drip’ style for which he became known. Around the time it was created (1948), Pollock stopped giving his paintings evocative titles and began instead to number them

‘Number 1A, 1948’, almost 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide, is currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where Pollock lived and studied.

As is clear from looking at the work, paint has been dripped and splattered across the canvas, creating a vivid, multicolored and chaotic work.

Pollock even gave the piece a personal touch, adding his handprints near the upper right, akin to an autograph.

‘Number 1A, 1948’ is also a quintessential example of his ‘action painting’, which emphasised the physical act of painting.

The team of scientists from MoMA, Stanford University and the City University of New York call it ‘one of his most iconic action paintings’.

‘Ropes of colour, drips of black, and pools of white coalesce into the layered dynamism that defines his style,’ they say.

While past work has identified the red and yellow pigments in the painting, the vibrant blue in the painting ‘has remained unassigned’.

To learn more, the researchers took scrapings of the blue paint and used lasers to scatter light and measure how the paint’s molecules vibrated.

Pollock, a lifelong alcoholic, infamously died after driving and crashing his car while drunk in August 1956. Pictured, creating one of his famous drip paintings

Manganese blue was also used to colour cement for swimming pools, but it was discontinued in the 1990s because of environmental concerns and its suspected toxicity when inhaled

That gave them a unique chemical fingerprint for the colour, which they’ve pinpointed as manganese blue, a synthetic pigment once a staple in artists’ paint boxes.

Manganese blue was also used to colour cement for swimming pools, but it was discontinued in the 1990s because of environmental concerns and its suspected toxicity.

Inhalation or ingestion of manganese blue can cause a nervous system disorder, according to the Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online.

A bright, azure blue first made in 1907, manganese blue is even today incredibly difficult to properly replicate by mixing existing paints.

The researchers also inspected the pigment’s chemical structure to understand how it produces such a vibrant shade.

Manganese blue’s pure hue is due to ‘excited’ reactions at the molecular level that filter nonblue light and fine-tune the colour, the experts say.

Their analysis, newly published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first confirmed evidence of Pollock using this specific blue.

Previous research had suggested that the turquoise from the painting could indeed be this colour, but the new study confirms it using samples from the canvas.

Lasers are used to determine a chemical fingerprint of samples of the blue paint from the Jackson Pollock painting ‘Number 1A, 1948’ in Stanford, California

Just like many of his other paintings, Pollock likely would have poured manganese blue directly onto the canvas from a stick or a can, instead of mixing paints on a palette beforehand.

Working on the floor in a spacious converted barn on Long Island, Pollock moved away from traditional artist’s oil paints and embraced lower viscosity commercial enamel paints that would pour easier.

Experts analysing the physics of Pollock’s technique have already reported that the artist had a ‘keen understanding’ of a classic phenomenon in fluid dynamics as he did so.

Pollock’s technique seems to intentionally avoid what is known as ‘coiling instability’ – the tendency of a viscous fluid to form curls and coils when poured onto a surface.

While the artist’s work may seem chaotic, Pollock rejected that interpretation and instead saw his work as methodical.

He once said: ‘The modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating.’

Around the time this particular work was created (1948), Pollock stopped giving his paintings evocative titles and began instead to number them.

His wife, artist Lee Krasner, later said: ‘Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a painting for what it is – pure painting.’