Dance History(s): Imagination as a Form of Study

Thomas F. DeFrantz and Annie-B Parson, Eds.

Dancing Foxes Press, Big Dance Theater, and Wesleyan University Press, 2024

Artists are vultures. We scavenge the past, taking what’s useful, and leaving the rest. I once heard a Pulitzer-Prize winning novelist sniff and say he’d never read George Eliot: Too boring. Not in his lineage.

So what happens when practicing artists become the historians of their form? Is the resulting story full of holes, or is it more tightly woven than the canonical one? In Dance History(s): Imagination as a Form of Study, Thomas F. DeFrantz and Annie-B Parson ask ten of their fellow dancer-choreographers, plus themselves, to “tell dance history as you know it to be,” and I was curious what this artist-centered approach would yield.

Something fun: right away this book asked me to dance. Unfolding the gorgeous map-sized introduction, silkscreened with haunting autumn leaves of glowing auburn and orange, I found myself walking around its perimeter, squatting on the floor, gasping softly with admiration.

And like many maps, I had to flip it over to get all the information: on the far side is DeFrantz’s ecstatic introduction, accompanied by Parson’s whimsical tarot card-esque illustrations. As DeFrantz explains, ten of the twelve contributors are people of color, and most are non-male; this matters because conventional dance history is riddled with omissions, biased toward white men, and, like most linear narratives, guilty of pretending that A leads inexorably to B and onward to C.

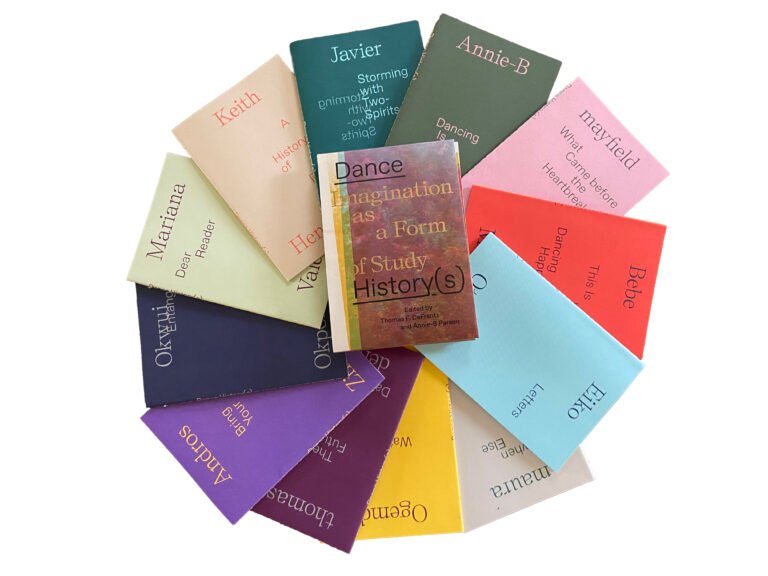

This project, then, is a corrective. Even the form of the book—twelve pamphlets, individually bound—pushes back against that usual structure of historical authority. Here, there can be no open or closing chapter, no tidy chronology. The pamphlets, spread out across my study floor in their saturated hues, reminded me of zines and Marxist bromides, handed out by true believers on the street: something urgent, personal, and political.

What emerges from the collection is a sense of dance history as invocation and list, elegy and collage. Nearly everyone writes a tribute to those dancers who shaped them, telling a history that leads inevitably to themselves, which would be obnoxious if there were only one author. But with twelve contributors, the book becomes polyphonic, singing that dance history goes here, and here, and here: to the border, the ocean, the ring shout; to Michael Jordan’s slam dunk, and the Lindy Hop, and big joyous parties in working-class Latinx Chicago.

Bebe Miller gives us directions from her childhood subway stop to Henry Street Settlement, where her intrepid mother brought her and her siblings for art and dance classes. Eiko Otake writes direct, touching letters “to those who danced and died,” including Dore Hayer, who killed herself when a knee injury threatened her dance career, and Kazuo Ohno, a founder of Butoh. Okwui Okpokwasili pays tribute to gestation and double dutch; Mariana Valencia invokes La Lupe, her friend’s hug, and the bar Julius’, each item lovingly footnoted, as if to say that this, too, is worthy of scholarly care.

Annie-B Parson comes closest to telling the textbook history of dance, though she narrates from a wise child’s perspective: “In the beginning everyone danced,” she writes, wry and knowing as she leads us briskly through ballet, modernism, postmodernism, and into the COVID era. Her history mourns, in part, the transition from dance as collective social practice to dance as Art, a concern that maura nguyễn donohue echoes when she writes of how dance became formalized into “us/do and them/watch;” donohue is also hilarious as she reflects on supporting her postmodern dance career by stripping in Times Square: “I’d already been naked all over downtown—why not get paid for a change, right?”

These personalized litanies, which all seem to converge on the Lower East Side in 1983, can feel insular. A relief, then, to turn to the writers who opt instead for a sociological lens. Keith Hennessy suggests that dance history is intertwined with the history of AIDS, urban real estate, and sex work. Andros Zins-Browne gives us “the dance of history” by contrasting two figures who were moved: Henry “Box” Brown, who famously shipped himself to freedom, and Freddie Gray, literally and deliberately driven to his death. Not for the nostalgic or sentimental, Zins-Browne wrestles with the violence in dance, and the way origin stories “can be coercive or indifferent, as well as nurturing.”

Others turn to narrative, that old, trusty, wily technology: mayfield brooks tells an Edenic fable of how the human desire for competition alienated us from the natural world. I found it overly sentimental, though their outrageous claim that plants were the ones who taught us to dance delighted me. More bracing is Thomas F. DeFrantz’s Afrofuturist day-in-the-life of an adjunct dance instructor in the twenty-second century. In it, TeleBrea teaches over ten thousand students the history of Black Social Dance simultaneously via neural implants that “nag” them into motion. Through TeleBrea, we learn our future history: the disasters to come and the dance forms they’ll inspire, such as the “be-a-man partner dances that had developed in the megajails of the 2060s.” What’s heartbreaking is how plausible it all sounds.

Javier Stell-Frésquez’s interrogation of the double erasure of Indigenous dances and Two-Spiritness is printed partially in reversed lettering, so that I had to keep getting up and standing before the bathroom mirror to read it. The gimmick was both cool and annoying, a trick that turns the question of self-revelation on the reader as I watched myself read about the history of US and Canadian efforts to eradicate Native dance.

These photo-essays, fables, and fictions were all clever, but none struck me as deeply as Ogemdi Ude’s joyful homage to the majorette dancers at Black Southern football games, who “enter with a strut” and embody “Black femme sensuality organized into eight counts.” In a brilliant paragraph, she eviscerates the contemporary dance world for lionizing Ohad Naharin, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Trisha Brown for supposedly pioneering, respectively, groove, complex counts, and “posturing in public space,” when the majorettes have been employing all these techniques for far longer. Ude’s essay is both celebration and corrective: why, she asks, was she asked during her dance training to forget the majorettes—this first, joyful way of moving—in favor of “Ohad, Anne, and Trisha?” Hers is history as reclamation, an affirmation of overlooked artistry.

After reading these pamphlets, I was pleasantly stirred up, buzzing with ideas, but confused, too, as if I had been in a seminar room with twelve professors shouting at once. Did I learn anything, I wondered. Was this history?

Surely it was not comfortable history, of the kind I knew best: comprehensive, linear, with artists all put in proper perspective, and the violence and racism neatly hidden. It was irritating to be discomfited, to have to get off my ass and unfold a map-sized introduction, or squint at words reflected in the bathroom mirror, to see myself blurry and faded, baffled and still, trying to understand words not necessarily printed for me. This was, perhaps, the most important lesson of all.