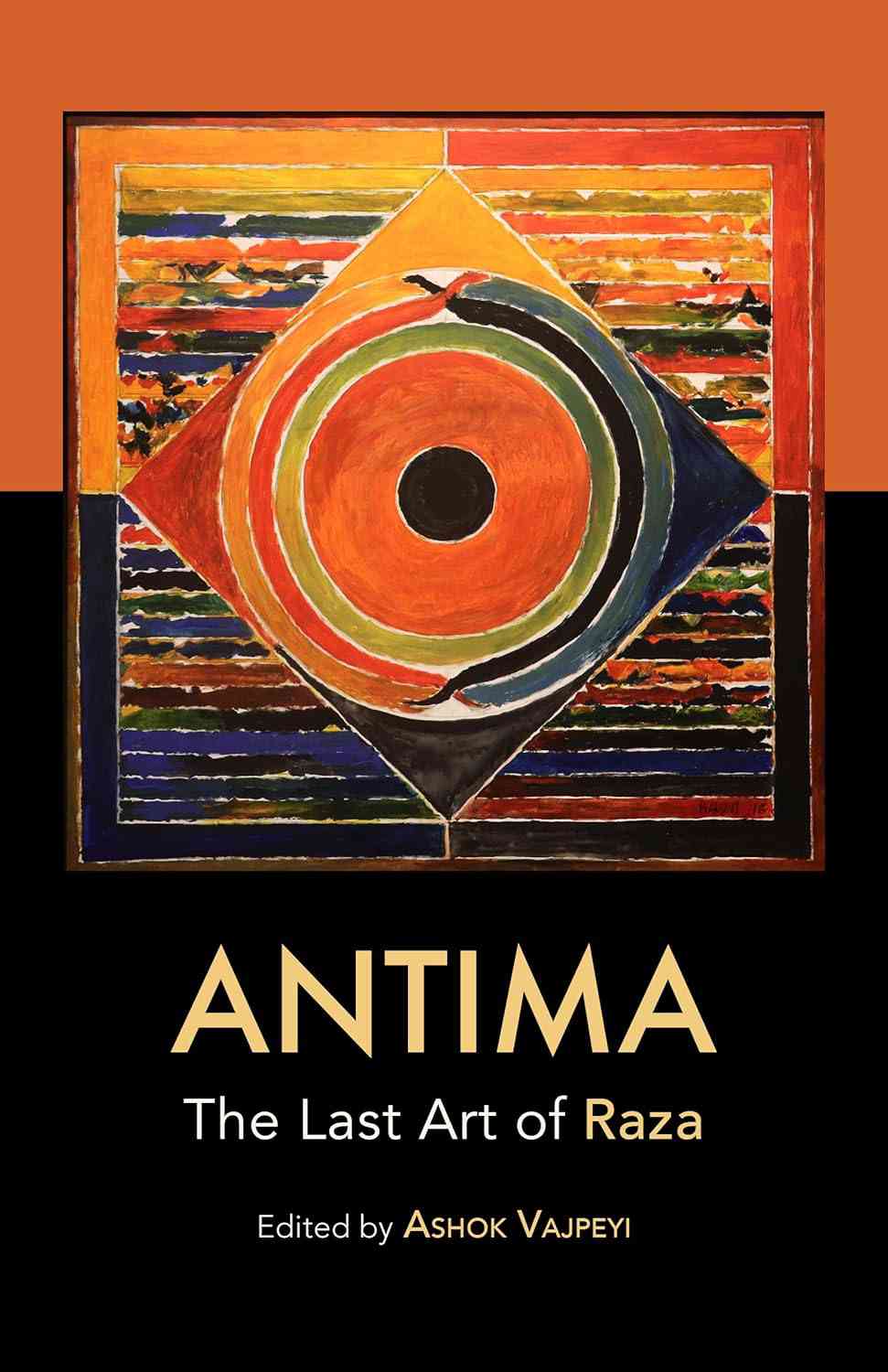

Syed Haider Raza’s lifelong search for the intangible continued till his last breath. His evolution over 60 years reflected this quest. In India, his preoccupation with evoking the essence of emotions and moods took over from an earlier quest to translate the visual onto the canvas. The simple experiences of night and day, joy and anguish, summer and winter that were his subjects, became silent companions that are felt in the flourish of his pliant brush. This final period of tones and expression was nestled within minimalist landscapes, a play of geometry and symbolism and a hint of the power of language – all of it imbued with hushed echoes of a life lived.

Raza’s landscapes in the last chapter of his life saw the use of colour in minimalist moorings, not so much as a tool but as subliminal strokes to evoke mood. From capturing the slow creeping of twilight, or the scorching angry summer sun, to villages set against the darkened recesses of forested hills – this last series had slim swathes of vivid primary colours and a few greys of rippling gravitas. As Raza’s friend, the poet Ashok Vajpeyi said, his love for dualities remained a constant companion. This friendship was dependent entirely on a love for the abstract and was littered with Vajpeyi’s poetry. The intangible, the corollaries, the conversations: everything morphed into paintings with poetic intensity.

Raza’s “Kanha Kisli”, named after the Kanha Tiger Reserve, is a riveting landscape that instantly brings alive his love for the Madhya Pradesh forests he roamed during his childhood. Raza’s father was a forest warden. Little did the father know that his son would one day be an icon in the history of Indian contemporary art.

Known for its plentiful big cat population, Kanha, established in 1955, is one of India’s oldest wildlife zones and has a reputation for being among the country’s best-managed forests. Raza loved reading news about Kanha and its efforts to bring animals back from extinction. Over the last decade, it brought the barasingha (a species of swamp deer) back from the brink of extinction in one of India’s most successful wildlife conservation efforts. How proud Raza was of this!

One of the reserve’s most charming claims to fame is that it served as the setting for Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 childhood classic The Jungle Book, a novel about a boy raised by wild wolves. Mentioning The Jungle Book would draw a smile from Raza and he would remark at the infinite capacity of human imagination. The painting, too, suggests a monsoon mood and appears somewhat nocturnal. The palette is one of soft effusion but it is the harmony of strokes blended into nimbus cloudy grey that adds to its evocation of a hushed musicality.

The pictorial space in Raza’s paintings became less structured while he explored the play of light and colour in nature. It was as if he had redefined the genre of the landscape painting, and in a minimalist mood, had centred strokes as its main premise. This stylistic turn is reinforced in works of this period.

In yet another 2012 work created in resonant reds, we are made to recall his years in 1962 when he spent a summer teaching in Berkeley, at the University of California. During his time in the United States, Raza was deeply impacted by the work of abstract expressionists like Sam Francis, Hans Hofmann and Mark Rothko. Speaking about this encounter in 2007 at the India International Centre, Delhi, in an interview with me over five days, he said: “Rothko’s work opened up lots of interesting associations for me. It was so different from the insipid realism of the European School. It was like a door that opened to another interior vision. Yes, I felt that I was awakening to the music of another forest, one of subliminal energy. Rothko’s works brought back the images of japmala, where the repetition of a word continues till you achieve a state of elated consciousness. Rothko’s works made me understand the feel for spatial perception.”

That word japmala is an important word. In some works we see hints of terracotta tints that create a synergy of the rudraksha from which the japmala is created. For Raza the japmala also evoked memories of Christian hymns (through the rosary), which he loved, especially the ones sung at Easter and Good Friday services in Gorbio, France. Raza had a deep love for devotion and worship, and his secular leanings created their own prism of perspective for a world order. His hands wove his love for colour into hymns of praise for the power of the divine.

In the sunset of his life, Raza revisited principles of Purush Prakriti, a topic deeply close to his heart. Within the construction of the square into vistas, he allowed his brush strokes and use of space to become definitive, thus creating expression within the frames. Raza’s use of quick-drying acrylic paints adds to the quicksilver slashes. It was also in this period of gestural expression, sometimes termed “lyrical abstraction”, that the artist turned to his homeland, India, for inspiration.

Drawing on his memories of growing up in the forests of central India was a perennial practice. Added to this, however, were his traditional Indian theories of colour and aesthetics, the use of Sanskrit and Urdu poetry, and teachings on visually-guided Buddhist meditation chanting practices that he picked up in early 2000s.

“More importantly, he continued to explore further possibilities of colour, making colour rather than any geometrical design or division the pivotal element around which his paintings moved. Also, colours were not being used as merely formal elements: they were emotionally charged. Their movements or consonances on the canvases seemed more and more to be provoked by emotions, reflecting or embodying emotive content. The earlier objectivity, or perhaps the distance started getting replaced or at least modified by an emergent subjectivity – colours started to carry the light load of emotions more than ever before.”

Excerpted with permission from Raza’s ‘Quest for the Intangible’, by Uma Nair in Antima: The Last Art of Raza, edited by Ashok Vajpeyi, Speaking Tiger Books.