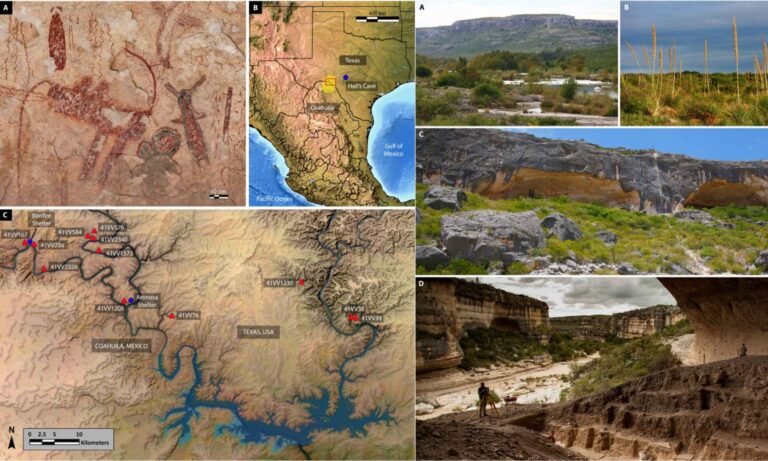

New dating of paint traces in Texas canyon shelters suggests some Pecos River-style cave paintings were initially commenced nearly 6,000 years ago.

Researchers studied limestone walls along the U.S.-Mexico border and found a steady tradition of ritual art that lasted millennia.

The work was led by Dr. Carolyn E. Boyd at Texas State University (TXST). Her research focuses on symbols and cave painting methods that show how hunter-gatherers passed beliefs between communities and generations.

These murals mix red ochre, black pigment, and yellow tones into scenes packed with human and animal figures.

Cave paintings in Lower Pecos

The canyonlands sit near the Rio Grande, and park guides lead visitors to Fate Bell Shelter. Overhangs in rock create shallow rooms, and the smooth walls offer broad surfaces for layered pigment.

Because the painters chose sheltered stone, their images still sit close to the places where rituals likely happened.

Pigments needed an organic binder so paint could grip stone for years. When that binder came from plants or animals, tiny bits of carbon stayed behind and later became datable evidence.

Modern analysts look for those carbon traces in cave paintings because bare mineral pigment often carries no signal for radiocarbon testing.

Dating the paint

In archaeology, radiocarbon dating, measuring time from carbon-14 decay, can date once-living material as old as about 60,000 years.

Dating cave paintings is hard because soot, plant oils, or groundwater can add carbon that was never in the paint.

To avoid mixing sources, the team sampled organic residue locked in paint layers rather than scraping the rock itself.

Reading layers carefully

They also used stratigraphy, reading time from stacked layers, to see which paint strokes sat on top of others.

Overlaps showed painters followed a consistent order for colors, suggesting they planned compositions instead of improvising each figure.

That kind of planning matters because it creates consistent meaning, and consistency helps messages survive when groups move often.

Numbers that anchor time

The study reports 57 direct radiocarbon dates and 25 mineral crust dates from murals across 12 sites.

Using Bayesian modeling, a method that blends dates with probabilities, they placed the start of the cave painting at between 5,760 and 5,385 years ago.

Their model suggests painting ended between 1,370 and 1,035 years ago, after a span of 4,095 to 4,780 years.

Why rules matter

Eight murals in the analysis followed a strict set of rules and an iconographic system of recurring symbols that carry shared meaning.

There are more than 200 murals across the region, with some of the shelters holding sweeping scenes. Many of these stretch across large rock faces and contain dense clusters of carefully painted figures arranged at an impressive scale.

The images were not random marks but the result of careful planning, reflecting artists who solved complex visual and symbolic problems while working within strict rules and shared traditions.

Cave painting symbols with staying power

Murals often show human-like figures, animals, and hard-to-read signs, and the same motifs appear across many shelters.

The study found stable messaging even as material culture, land use, and climate changed in the surrounding canyonlands.

When a community keeps symbols steady for centuries, each painter can add meaning without confusing people who return later.

Themes without writing

Researchers describe the tradition as a cosmovision, a shared view of how the universe works, expressed through repeated scenes.

Without written texts, shared routines and repetition can help people remember myth, timing, and proper behavior during group ceremonies.

One theme remains consistent across the canyon walls, as the imagery continues to carry stories that are still recognized, remembered, and shared by Indigenous communities today.

Climate kept cave paintings safe

The canyonlands are dry enough that pigments can last, and the shelters protect paint from constant water flow.

Stable temperatures and limited sunlight under the rock roofs slow many chemical changes that would otherwise fade colors.

Even in arid country, flash floods, smoke, and careless touching can erase details that never return.

Work that risks damage

Paint dating usually needs a pinhead-sized sample, so researchers must pick spots where loss will not ruin meaning.

Teams now combine tiny samples with high-resolution photography, so they can check results against what the full panel shows.

Digital microscopes let scientists measure paint thickness and grain, and that supports decisions about what to sample.

Respecting living heritage

Some Indigenous viewers see the figures as ancestral deities, sacred beings tied to creation, rather than silent art on stone.

Because that meaning still matters, researchers often work with Indigenous consultants before interpreting symbols or sharing images publicly.

Those discussions can influence where samples come from, which sites stay off-limits, and how results return to communities.

Questions still open

The people who painted these scenes left no names, and their exact cultural identities remain uncertain today.

Future work at TXST may compare pigment recipes and brush marks across shelters, looking for links between family groups or trade routes.

Researchers also want to match mural dates with local climate records, to test whether droughts or abundance changed ritual needs.

What cave paintings change

Forager societies are sometimes treated as simple, yet this work shows they built complex systems of meaning and teaching.

In the paper, the authors propose that the murals helped pass a sophisticated metaphysics that later informed Mesoamerican agriculturalists.

That argument puts deep time behind cultural connections that many communities already recognize across the borderlands.

Careful dating can turn old debates into testable timelines, and it can also show respect for art that endures.

As research continues, protection and partnership will decide whether these painted shelters stay intact for future study and visitors.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–