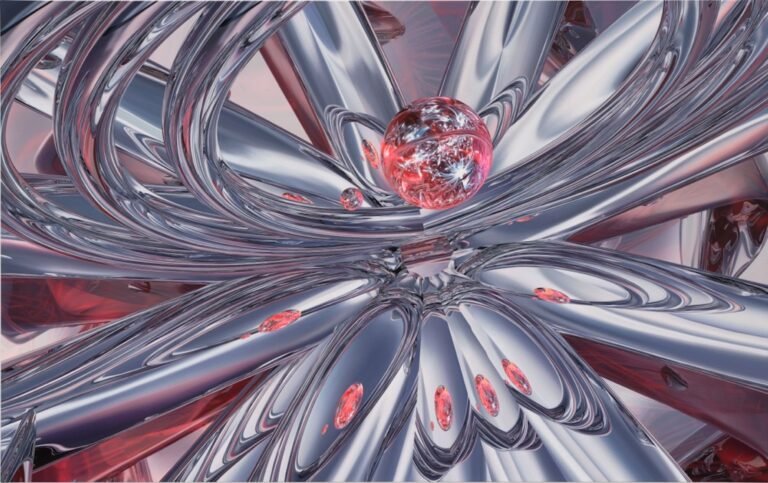

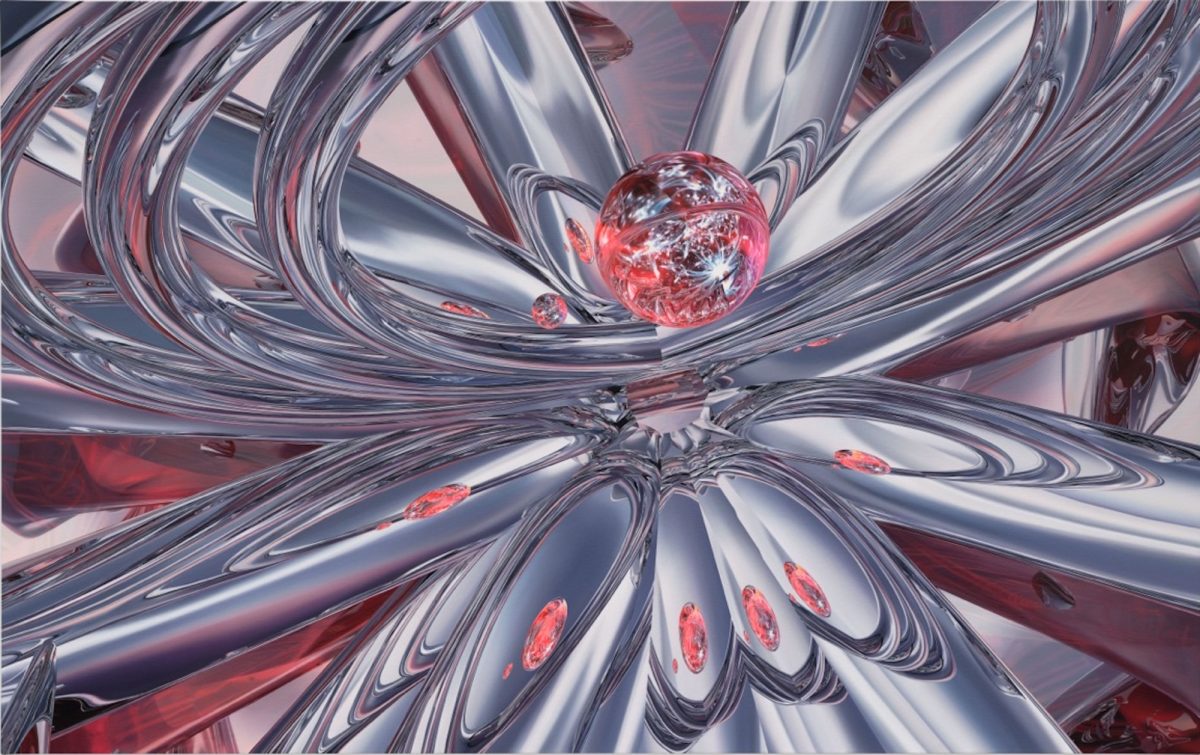

Walking into Memory Bands, the exhibition of Chanel Khoury’s paintings at James Fuentes’ gallery in Los Angeles, you might initially assume the works on the walls are digital images — pixel-perfect computer renderings of orbs, arches, mirrors, and water. Perspectives shift, images repeat and recede, and the compositions seem generated by an algorithmic mind rather than a human hand.

But the images are fully hand-painted, and they are Khoury’s articulation of 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s “objectification of will”— the idea that every object, from teeth to galaxies, embodies a specific striving or purpose. Khoury isn’t the first artist to translate Schopenhauer’s ideas, but she isn’t leaning into abstraction. Her symbols are legible; her presentation, intentionally straightforward. She aims to reproduce divinity without tethering her work to any specific faith.

“The idea of objects being conscious was something that I wanted to explore with painting,”

she said in an interview at the gallery.

“I’m a vessel and it has to be processed through my body and brain… for it to actually breathe.”

Khoury, 27, a Rhode Island native who recently moved to Los Angeles, describes herself as a “sculptor trapped in a painter’s body,” someone who visualizes in 3D. She builds virtual worlds that attempt to give form to Schopenhauer’s ideas.

That she spends months — sometimes a full year — hand-painting a single digital model isn’t masochism; it’s philosophical necessity. Her process mirrors her thinking: the computer generates forms she has previously sketched, but only her hand can make them “breathe” on canvas.

“I’m mimicking a machine and the machine’s mimicking God,”

she said.

“People who know how to 3D model look at what I’m doing and say, ‘That’s going to break your computer.’”

Khoury began this approach as a student at New York University, where she double-majored in philosophy and art. Through a combination of painting and 3D modeling, she arrived at a process that gives her the control she craves. She isn’t interested in producing beautiful computer-generated images alone; she needs to understand — and remake — them in paint. “I have to be scared of it,” she explained. “I’m relearning the image by hand. I need every part of the painting to be accounted for and adorned.”

Her work aligns with the 21st-century movement known as devirtualization, the translation of virtual concepts and digital culture into physical form through traditional techniques. The paintings in the exhibition feature the ctenophore (or comb jelly) as a recurring motif — a bioluminescent marine invertebrate dating back 740 million years. It resembles digital ectoplasm, serving as a light source throughout Khoury’s digital skies. Its ancient-yet-futuristic appearance makes it an ideal emblem for work exploring consciousness, perception, and form.

To build these virtual worlds, Khoury uses Cinema 4D and Rhino, architectural software that lets her specify exact lighting conditions — “Egypt 1948, 10:30 PM,” for example —and combine impossible materials that push the software beyond its limits. The resulting computational glitches become integral to her aesthetic. “I’m essentially creating these vast spaces with my own materials,” she said, demonstrating her process on a laptop. “What if I made this chrome and this translucent glass? Or half chrome, half glass?”

She generates hundreds of digital versions of each painting, photographing different angles “almost like archaeology” before selecting one to paint. The resulting works range from architectural to organic. The anchor of the show, Nexus (2023–24), took eighteen months to complete. An archway suspended above a rectangular abyss, its floating spheres recur and distort in their own reflections. It functions as both altarpiece and portal, and its symmetrical composition defies traditional painting norms.

“We’re biologically designed to be attracted to symmetry,”

Khoury noted.

“Why would I not make a symmetrical painting? It’s the most attractive thing you can do in terms of the subconscious.”

Some spheres reflect their environment; others reveal images just out of reach. This ambiguity is deliberate: Khoury wants to visualize the uncertainty of perception, though she considers the spheres “all-knowing entities.” Nexus is in conversation with ball is life (lodestar) (2025), in which an orb crashes through space as if ready to transcend into the painting in front of it. She says this work reveals her sculptural leanings — it sits atop a pedestal — and represents the “heartbeat of the show.”

She describes wishing room (2024–25) as an echo of a siphonophore, a colonial marine organism visualized as a recurring coil whose arms signify its self-cloning structure. Rendered in purples, greens, and pinks, the painting features descending orbs that intersect with oval forms acting as a “receiver.” The ctenophore appears again as a sky object and light source, distorting across the sky and into the reflective scene.

“These are definitely the least still paintings I’ve ever made,” Khoury said. “They’re menacing, and they have a heartbeat to them.”

When asked about AI — a natural question given the digital aesthetic—Khoury is unequivocal: “I think art should be art. What makes art human is the fact that humans make it.”

This tension — between divine perfection and human imperfection, ancient creatures and digital glitches, machine precision and hand-painted variation — gives Khoury’s work its resonance. She isn’t merely reproducing digital aesthetics in paint; she’s using one of the oldest mediums to visualize consciousness itself, revealing what it looks like when will becomes form, when the immaterial manifests as matter.

“Even though I’m hiding the human hand, my hand is what makes them breathe,”

Next year, she will present new work at Loyal Gallery’s new London space, featuring “a lot of water” — lighter, more fluid compositions after what she calls “the dark side of my soul” explored in Memory Bands.

For now, the paintings at James Fuentes make their argument: that in an age of instant AI-generated imagery, profound value remains in spending a year and a half translating impossible virtual worlds into physical paint—not despite the difficulty, but because of it.

Chanel Khoury, Memory Bands 8th November 2025 – 13th December 2025 James Fuentes Gallery, L.A.

Categories

Tags

Author

Jane Horowitz is a Los Angeles-based arts journalist whose writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, L.A. Daily News, Whitehot magazine and Art NowLA, among others. Her reporting spans the contemporary art world, with interviews featuring artists such as Amy Sherald and Elmgreen & Dragset. In addition to her editorial work, Jane brings two decades of experience in digital content strategy and management. You can find samples of her writing at janehorowitz.com/writing.